The Kan Extension Seminar II continues and this week, we discuss Jon Beck’s “Distributive Laws”, which was published in 1969 in the proceedings of the Seminar on Triples and Categorical Homology Theory, LNM vol 80. In the previous Kan seminar post, Evangelia described the relationship between Lawvere theories and finitary monads, along with two ways of combining them (the sum and tensor) that are very natural for Lawvere theories but less so for monads. Distributive laws give us a way of composing monads to get another monad, and are more natural from the monad point of view.

Beck’s paper starts by defining and characterizing distributive laws. He then describes the category of algebras of the composite monad. Just as monads can be factored into adjunctions, he next shows how distributive laws between monads can be “factored” into a “distributive square” of adjunctions. Finally, he ends off with a series of examples.

Before we dive into the paper, I would like to thank Emily Riehl, Alexander Campbell and Brendan Fong for allowing me to be a part of this seminar, and the other participants for their wonderful virtual company. I would also like to thank my advisor James Zhang and his group for their insightful and encouraging comments as I was preparing for this seminar.

First, some differences between this post and Beck’s paper:

-

I’ll use the standard, modern convention for composition: the composite $\mathbf{X} \overset{F}{\to} \mathbf{Y} \overset{G}{\to} \mathbf{Z}$ will be denoted $GF$. This would be written $FG$ in Beck’s paper.

-

I’ll use the terms “monad” and “monadic” instead of “triple” and “tripleable”.

-

I’ll rely quite a bit on string diagrams instead of commutative diagrams. These are to be read from right to left and top to bottom. You can learn about string diagrams through these videos or this paper (warning: they read string diagrams in different directions than this post!).

-

All constructions involving the category of $S$-algebras, $\mathbf{X}^S$, will be done in an “object-free” manner involving only the universal property of $\mathbf{X}^S$.

The last two points have the advantage of making the resulting theory applicable to $2$-categories or bicategories other than $\mathbf{Cat}$, by replacing categories/ functors/ natural transformations with 0/1/2-cells.

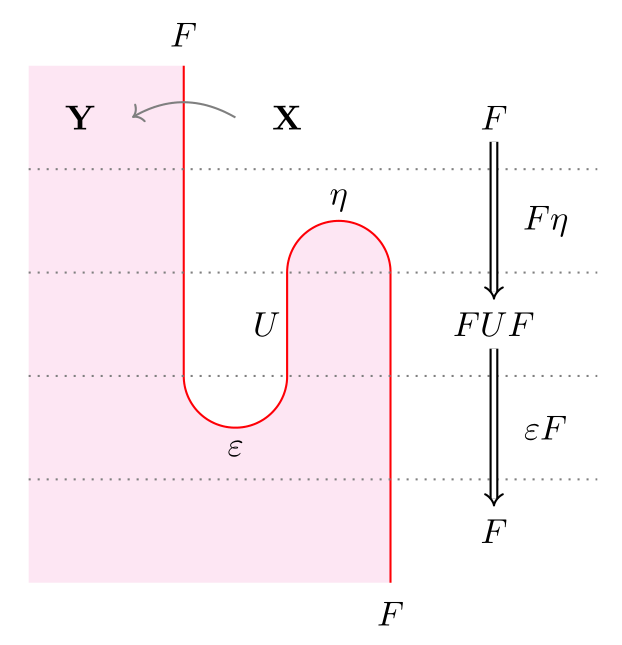

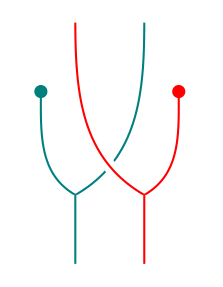

Since string diagrams play a key role in this post, here’s a short example illustrating their use. Suppose we have functors $F: \mathbf{X} \to \mathbf{Y}$ and $U: \mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}$ such that $F \dashv U$. Let $\eta: 1^{\mathbf{X}} \Rightarrow{UF}$ be the unit and $\varepsilon: FU \Rightarrow 1^{\mathbf{Y}}$ the counit of the adjunction. Then the composite $F \overset{F \eta}{\Rightarrow} FUF \overset{\varepsilon F}{\Rightarrow} F$ can be drawn thus:

Most diagrams in this post will not be as meticulously labelled as the above. Unlabelled white regions will always stand for a fixed category $\mathbf{X}$. If $F \dashv U$, I’ll use the same colored string to denote them both, since they can be distinguished from their context: above, $F$ goes from a white to red region, whereas $U$ goes from red to white (remember to read from right to left!). The composite monad $UF$ (not shown above) would also be a string of the same color, going from a white region to a white region.

Motivating examples

Example 1: Let $S$ be the free monoid monad and $T$ be the free abelian group monad over $\mathbf{Set}$. Then the elementary school fact that multiplication distributes over addition means we have a function $STX \to TSX$ for $X$ a set, sending $(a+b)(c+d)$, say, to $ac+ad+bc+bd$. Further, the composition of $T$ with $S$ is the free ring monad, $TS$.

Example 2: Let $A$ and $B$ be monoids in a braided monoidal category $(\mathcal{V}, \otimes, 1)$. Then $A \otimes B$ is also a monoid, with multiplication:

\[A \otimes B \otimes A \otimes B \xrightarrow{A \otimes tw_{BA} \otimes B} A \otimes A \otimes B \otimes B \xrightarrow{\mu_A \otimes \mu_B} A \otimes B,\]where $tw_{BA}: B \otimes A \to A \otimes B$ is provided by the braiding in $\mathcal{V}$.

In example 1, there is also a monoidal category in the background: the category $\left(\mathbf{End}(\mathbf{Set}), \circ, \text{Id}\right)$ of endofunctors on $\mathbf{Set}$. But this category is not braided – which is why we need distributive laws!

Distributive laws, composite and lifted monads

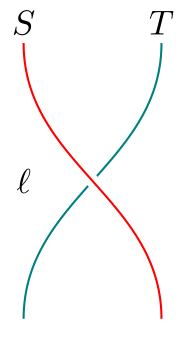

Let $(S,\eta^S, \mu^S)$ and $(T,\eta^T,\mu^T)$ be monads on a category $\mathbf{X}$. I’ll use Scarlet and Teal strings to denote $S$ and $T$, resp., and white regions will stand for $\mathbf{X}$.

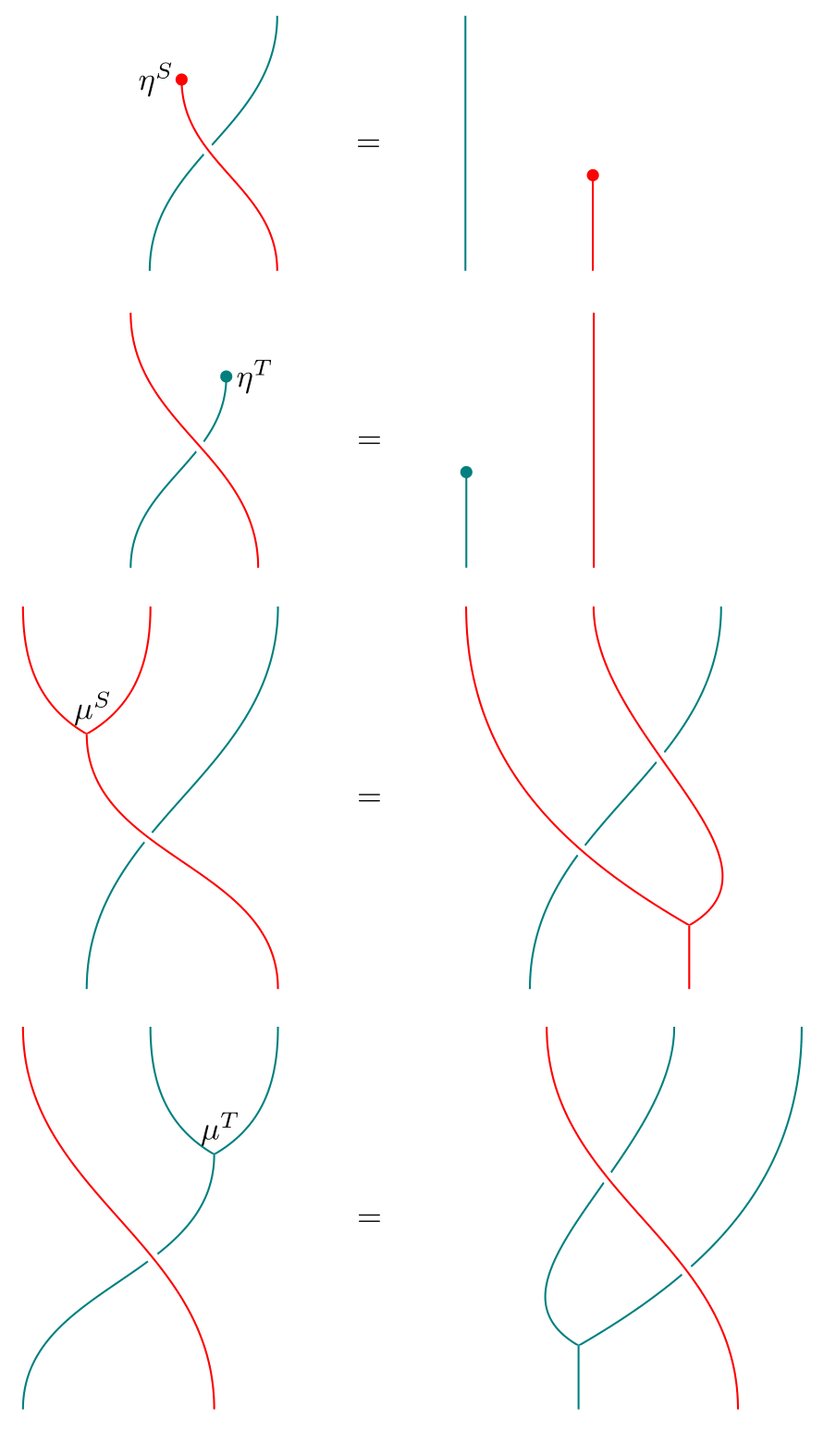

A distributive law of $S$ over $T$ is a natural transformation $\ell:ST \Rightarrow TS$, denoted

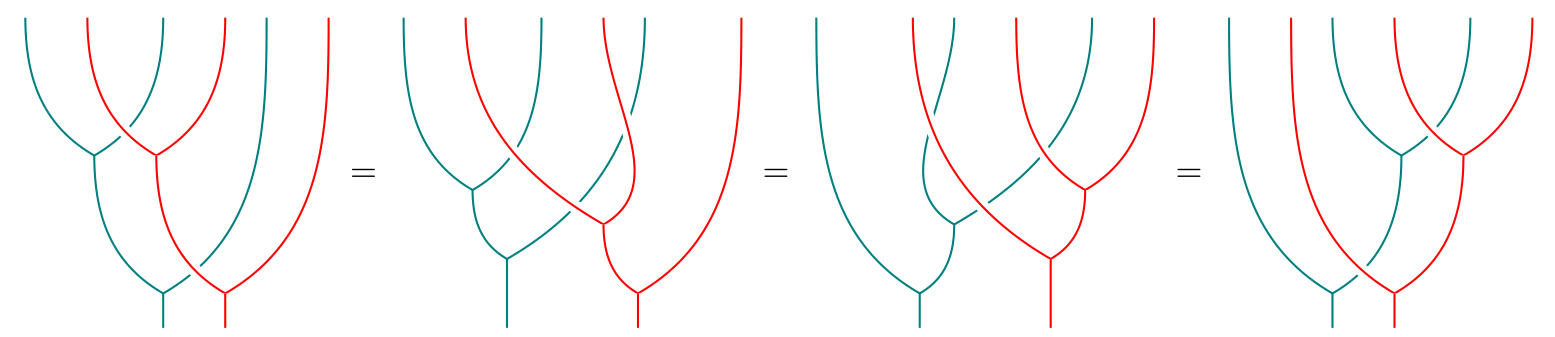

satisfying the following equalities:

A distributive law looks somewhat like a braiding in a braided monoidal category. In fact, it is a local pre-braiding: “local” in the sense of being defined only for $S$ over $T$, and “pre” because it is not necessarily invertible.

As the above examples suggest, a distributive law allows us to define a multiplication $m:TSTS \Rightarrow TS$:

It is easy to check visually that this makes $TS$ a monad, with unit $\eta^T \eta^S$. For instance, the proof that $m$ is associative looks like this:

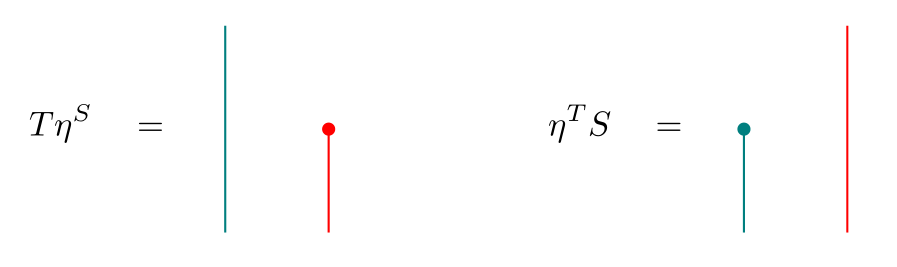

Not only is $TS$ a monad, we also have monad maps $T \eta^S: T \Rightarrow TS$ and $\eta^T S: S \Rightarrow TS$:

Asserting that $T \eta^S$ is a monad morphism is the same as asserting these two equalities:

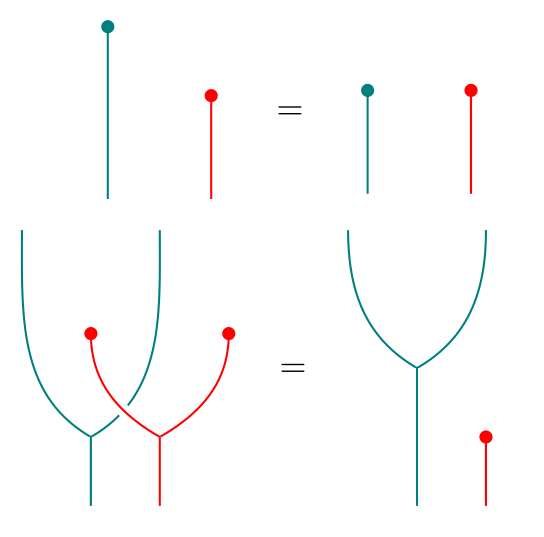

Similar diagrams hold for $\eta^T S$. Finally, the multiplication $m$ also satisfies a middle unitary law:

To get back the distributive law, we can simply plug the appropriate units at both ends of $m$:

This last procedure (plugging units at the ends) can be applied to any $m’:TSTS \Rightarrow TS$. It turns out that if $m’$ happens to satisfy all the previous properties as well, then we also get a distributive law. Further, the (distributive law $\to$ multiplication) and (multiplication $\to$ distributive law) constructions are mutually inverse:

Theorem The following are equivalent: (1) Distributive laws $\ell:ST \Rightarrow TS$; (2) multiplications $m:TSTS \Rightarrow TS$ such that $(TS, \eta^T \eta^S, m)$ is a monad, $T\eta^S$ and $\eta^T S$ are monad maps, and the middle unitary law holds.

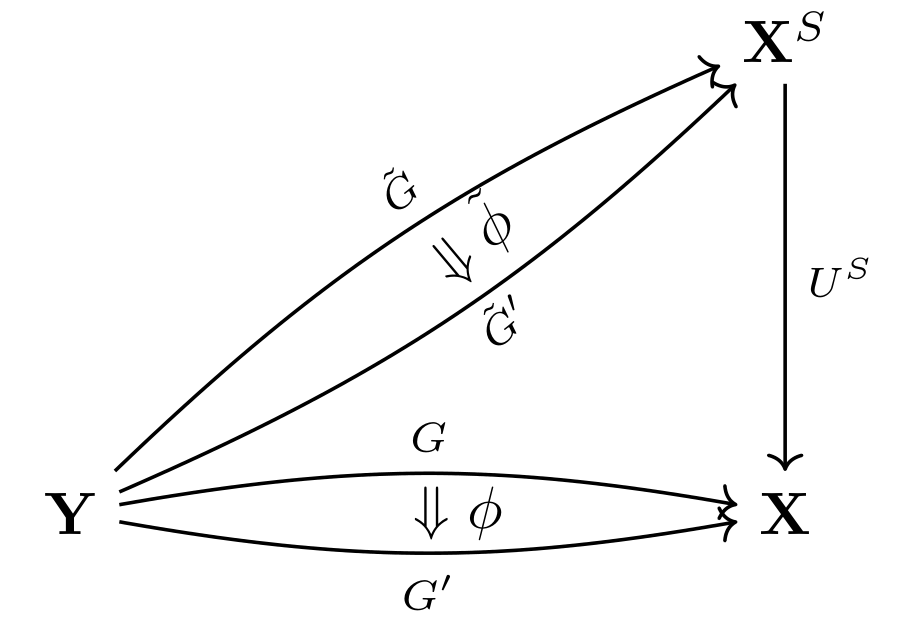

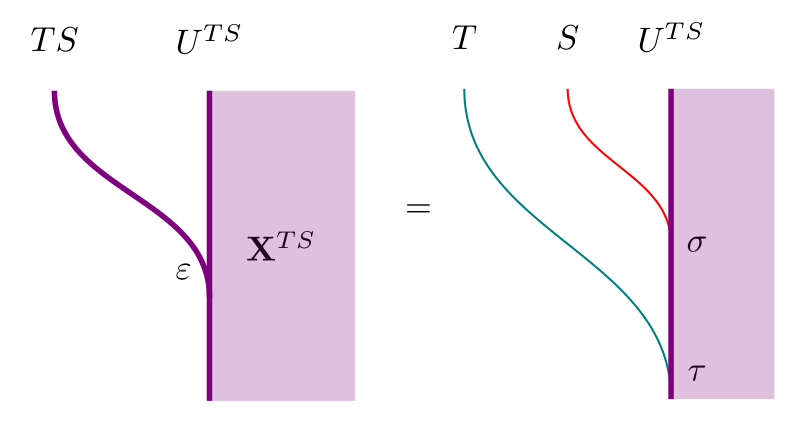

In addition to making $TS$ a monad, distributive laws also let us lift $T$ to the category of $S$-algebras, $\mathbf{X}^S$. Before defining what we mean by “lift”, let’s recall the universal property of $\mathbf{X}^S$: Let $\mathbf{Y}$ be another category; then there is an isomorphism of categories between $\mathbf{Funct}(\mathbf{Y}, \mathbf{X}^S)$ – the category of functors $\tilde{G}: \mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}^S$ and natural transformations between them, and $S$-$\mathbf{Alg}(\mathbf{Y})$ – the category of functors $G: \mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}$ equipped with an $S$-action $\sigma: SG \Rightarrow G$ and natural transformations that commute with the $S$-action.

Given $\tilde{G}: \mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}^S$, we get a functor $\mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}$ by composing with $U^S$. This composite $U^S \tilde{G}$ has an $S$-action given by the canonical action on $U^S$. The universal property says that every such functor $G: \mathbf{Y} \to \mathbf{X}$ with an $S$-action is of the form $U^S \tilde{G}$. Similar statements hold for natural transformations. We will call $\tilde{G}$ and $\tilde{\phi}$ lifts of $G$ and $\phi$, resp.

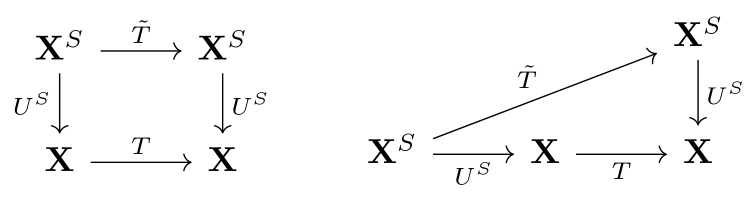

A monad lift of $T$ to $\mathbf{X}^S$ is a monad $(\tilde{T}, \tilde{\eta}^T,\tilde{\mu}^T)$ on $\mathbf{X}^S$ such that

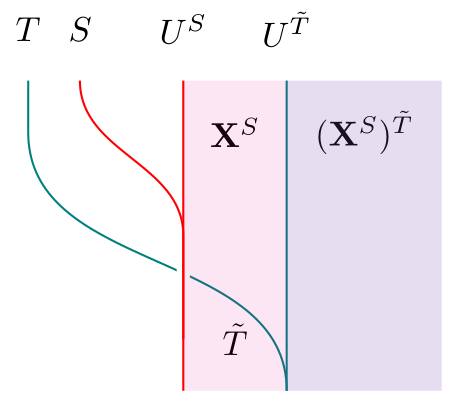

\[U^S \tilde{T} = T U^S, \qquad U^S \tilde{\eta}^T = \eta^T U^S, \qquad U^S \tilde{\mu}^T = \mu^T U^S.\]We may express $U^S \tilde{T} = T U^S$ via the following equivalent commutative diagrams:

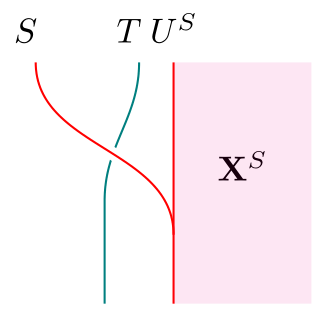

The diagram on the right makes it clear that $\tilde{T}$ being a monad lift of $T$ is equivalent to $\tilde{T}, \tilde{\eta}^T, \tilde{\mu}^T$ being lifts of $TU^S, \eta^T U^S,\mu^T U^S$, resp. Thus, to get a monad lift of $T$, it suffices to produce an $S$-action on $TU^S$ and check that it is compatible with $\eta^T U^S$ and $\mu^T U^S$. We may simply combine the distributive law with the canonical $S$-action on $U^S$ to obtain the desired action on $TU^S$:

(Recall that the unlabelled white region is $\mathbf{X}$. In subsequent diagrams, we will leave the red region unlabelled as well, and this will always be $\mathbf{X}^S$. Similarly, teal regions will denote $\mathbf{X}^T$.)

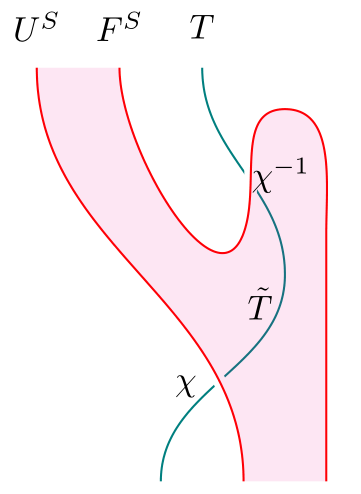

Conversely, suppose we have a monad lift $\tilde{T}$ of $T$. Then the equality $U^S \tilde{T} = T U^S$ can be expressed by saying that we have an invertible natural transformation $\chi: U^S \tilde{T} \Rightarrow TU^S$. Using $\chi$ and the unit and counit of the adjunction $F^S \dashv U^S$ that gives rise to $S$, we obtain a distributive law of $S$ over $T$:

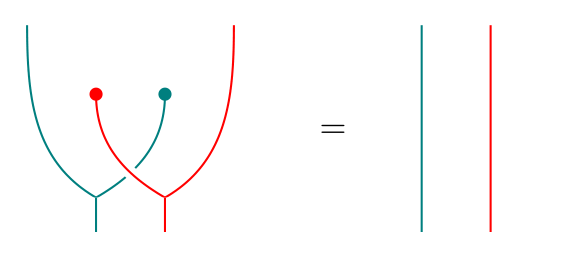

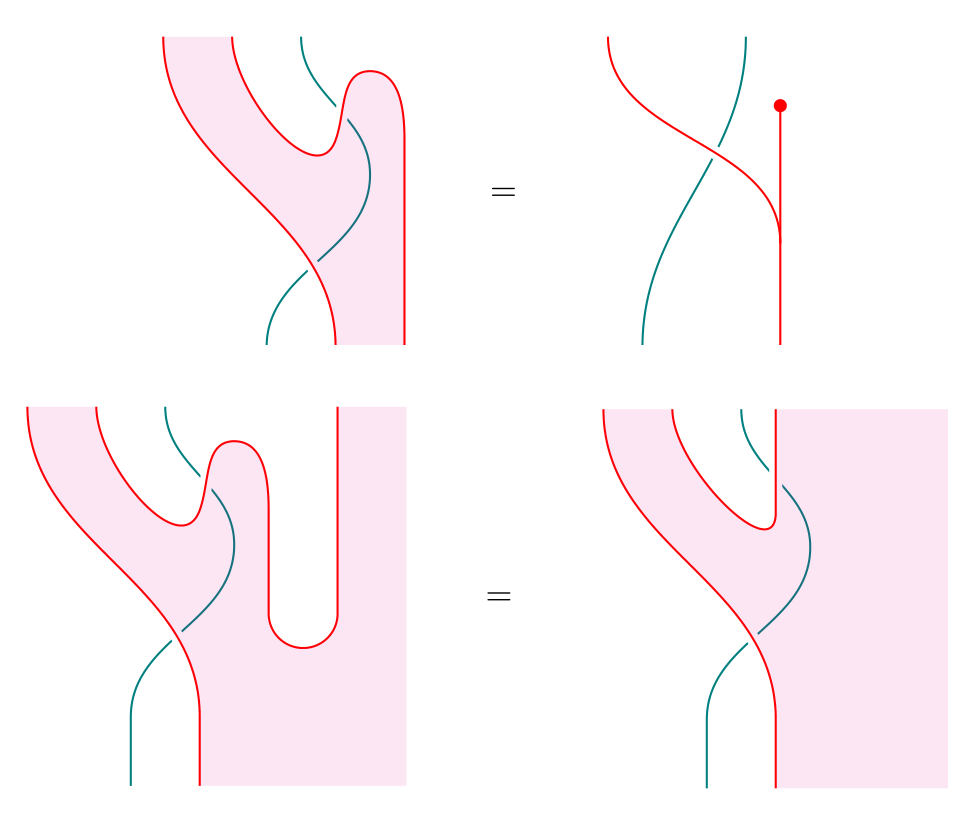

The key steps in the proof that these constructions are mutually inverse are contained in the following two equalities:

The first shows that the resulting distributive law in the (distributive law $\to$ monad lift $\to$ distributive law) construction is the same as the original distributive law we started with. The second shows that in the (monad lift $\tilde{T}$ $\to$ distributive law $\to$ another lift $\tilde{T}’$) construction, the $S$-action on $U^S \tilde{T}’$ (LHS of the equation) is the same as the original $S$-action on $U^S \tilde{T}$ (RHS), hence $\tilde{T} = \tilde{T}’$ (by virtue of being lifts, $\tilde{T}$ and $\tilde{T}’$ can only differ in their induced $S$-actions on $U^S \tilde{T} = U^S \tilde{T}’ = TU^S$). We thus have another characterization of distributive laws:

Theorem The following are equivalent: (1) Distributive laws $\ell:ST \Rightarrow TS$; (3) monad lifts of $T$ to $\mathbf{X}^S$.

In fact, the converse construction did not rely on the universal property of $\mathbf{X}^S$, and hence applies to any adjunction giving rise to $S$ (with a suitable definition of a monad lift of $T$ in this situation). In particular, it applies to the Kleisli adjunction $F_S \dashv U_S$. Since the Kleisli category $\mathbf{X}_S$ is equivalent to the subcategory of free $S$-algebras (in the classical sense) in $\mathbf{X}^S$, this means that to get a distributive law of $S$ over $T$, it suffices to lift $T$ to a monad over just the free $S$-algebras! (Thanks to Jonathan Beardsley for pointing this out!) The resulting distributive law may be used to get another lift of $T$, but we should not expect this to be the same as the original lift unless the original lift was “monadic” to begin with, in the sense of being a lift to $\mathbf{X}^S$.

There are two further characterizations of distributive laws that are not mentioned in Beck’s paper, but whose equivalences follow easily. Eugenia Cheng in Distrbutive laws for Lawvere theories states that distributive laws of $S$ over $T$ are also equivalent to extensions of $S$ to a monad $\tilde{S}$ on the Kleisli category $\mathbf{X}_T$. This follows by duality from the above theorem, since $\mathbf{X}_T = (\mathbf{X}^{op})^T$. Finally, Ross Street’s The formal theory of monads (which was also covered in a previous Kan Extension Seminar post) says that distributive laws in a $2$-category $\mathbf{K}$ are precisely monads in $\mathbf{Mnd}(\mathbf{K})$. It is a fun and easy exercise to draw string diagrams for objects of $\mathbf{Mnd}(\mathbf{Mnd}(\mathbf{K}))$; it becomes visually obvious that these are the same as distributive laws.

Algebras for the composite monad

After characterizing distributive laws, Beck characterizes the algebras for the composite monad $TS$.

Just as a morphism of rings $R \to R’$ induces a “restriction of scalars” functor $R’$-$\mathbf{Mod} \to R$-$\mathbf{Mod}$, the monad maps $T \eta^S: T \Rightarrow TS$ and $\eta^T S: S \Rightarrow TS$ induce functors $\hat{U}^{TS}: \mathbf{X}^{TS} \to \mathbf{X}^T$ and $\tilde{U}^{TS}: \mathbf{X}^{TS} \to \mathbf{X}^S$.

Equivalently, we have $S$- and $T$-actions on $U^{TS}$, which we call $\sigma: SU^{TS} \Rightarrow U^{TS}$ and $\tau: T U^{TS} \Rightarrow U^{TS}$. Let $\varepsilon: TS\, U^{TS} \Rightarrow U^{TS}$ be the canonical $TS$-action on $U^{TS}$. The middle unitary law then implies that $\varepsilon = T\sigma \cdot \tau$:

Further, $\sigma$ is distributes over $\tau$ in the following sense:

The properties of these actions allow us to characterize $TS$-algebras:

\[\mathbf{X}^{TS} \cong (\mathbf{X}^S)^{\tilde{T}}\]Theorem The category of algebras for $TS$ coincides with that of $\tilde{T}$:

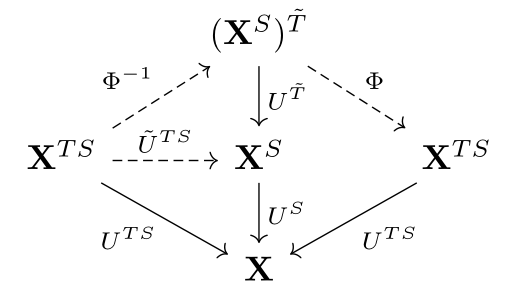

To prove this, Beck constructs $\Phi: (\mathbf{X}^{S})^{\tilde{T}} \to \mathbf{X}^{TS}$ and its inverse $\Phi^{-1}: \mathbf{X}^{TS} \to (\mathbf{X}^S)^{\tilde{T}} $. These constructions are best summarized in the following diagram of lifts:

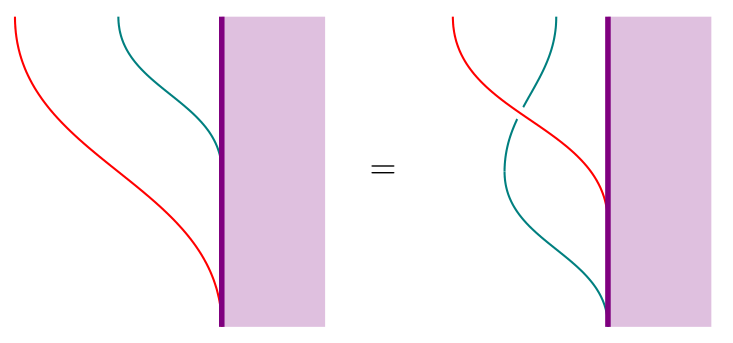

On the left half of the diagram, we see that to get $\Phi^{-1}$, we must first produce a functor $\tilde{U}^{TS}: \mathbf{X}^{TS} \to \mathbf{X}^S$ with a $\tilde{T}$-action. We already have $\tilde{U}^{TS}$ as a lift of $U^{TS}$, given by the $S$-action $\sigma$. We also have the $T$-action $\tau$ on $U^{TS}$, which $\sigma$ distributes over. This is precisely what is required to get a lift of $\tau$ to a $\tilde{T}$-action $\tilde{\tau}$ on $\tilde{U}^{TS}$, which gives us $\Phi^{-1}$.

On the right half of the diagram, to get $\Phi$ we need to produce a functor $(\mathbf{X}^{S})^{\tilde{T}} \to \mathbf{X}$ with a $TS$-action. The obvious functor is $U^S U^{\tilde{T}}$, and we get an action by using the canonical actions of $S$ on $U^S$ and $\tilde{T}$ on $U^{\tilde{T}}$:

All that’s left to prove the theorem is to check that $\Phi$ and $\Phi^{-1}$ are inverses. In a similar fashion, we can prove the dual statement (again found in Cheng’s paper but not Beck’s):

\[\mathbf{X}_{TS} \cong (\mathbf{X}_T)_{\tilde{S}}\]Theorem The Kleisli category of $TS$ coincides with that of $\tilde{S}$:

Distributivity for adjoints

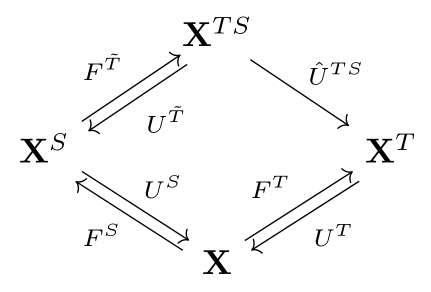

From now on, we identify $\mathbf{X}^{TS}$ with $(\mathbf{X}^S)^{\tilde{T}}$. Under this identification, it turns out that $\tilde{U}^{TS} \cong U^{\tilde{T}}$, and we obtain what Beck calls a distributive adjoint situation comprising 3 pairs of adjunctions:

For this to qualify as a distributive adjoint situation, we also require that both composites from $\mathbf{X}^{TS}$ to $\mathbf{X}$ are naturally isomorphic, and both composites from $\mathbf{X}^S$ to $\mathbf{X}^T$ are naturally isomorphic. This can be expressed in the following diagram by requiring both blue circles to be mutually inverse, and both red circles to be mutually inverse:

(Recall that colored regions are categories of algebras for the corresponding monads, and the cap and cup are the unit and counit of $F^S \dashv U^S$.)

This diagram is very similar to the diagram for getting a distributive law out of a lift $\tilde{T}$, and it is easy to believe that any such distributive adjoint situation (with 3 pairs of adjoints - not necessarily monadic - and the corresponding natural isomorphisms) leads to a distributive law.

Finally, suppose the “restriction of scalars” functor $\hat{U}^{TS}$ has an adjoint. This adjoint behaves like an “extension of scalars” functor, and Beck fittingly calls it $(\,) \otimes_S F^T$ at the start of his paper. I’ll use $\hat{F}^{TS}$ instead, to highlight its relationship with $\hat{U}^{TS}$.

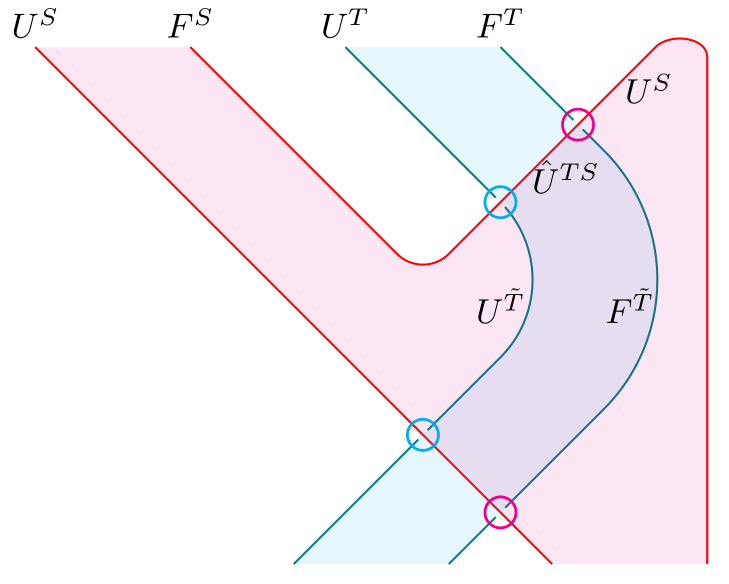

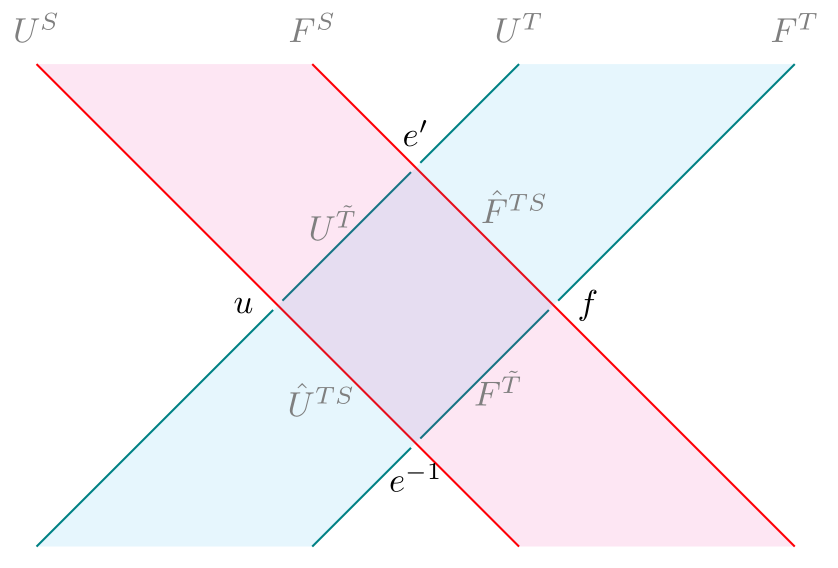

In such a situation, we get an adjoint square consisting of 4 pairs of adjunctions. By drawing these 4 adjoints in the following manner, it becomes clear which natural transformations we require in order to get a distributive law:

(Recall that $S = U^S F^S$ and $T = U^T F^T$, so this is a “thickened” version of what a distributive law looks like.)

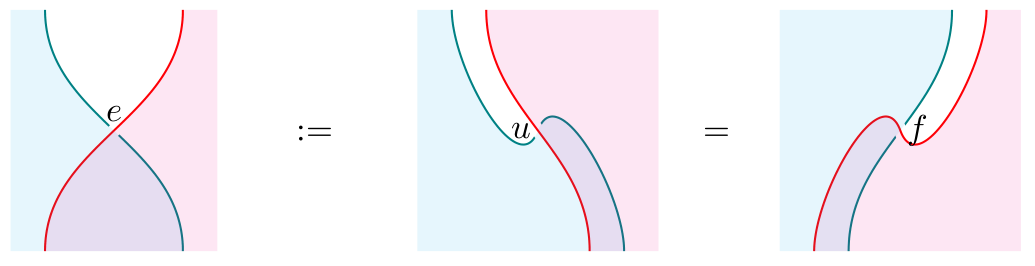

It turns out that given the natural transformation $u$ between the composite right adjoints $U^S U^{\tilde{T}}$ and $U^T \hat{U}^{TS}$, we can get the natural transformation $f$ as the mate of $u$ between the corresponding composite left adjoints $\hat{F}^{TS} F^T$ and $F^{\tilde{T}} F^S$. Note that $f$ is invertible if and only if $u$ is. We may use $u$ or $f$, along with the units and counits of the relevant adjunctions, to construct $e$:

But $e$ is in the wrong direction, so we have to further require that $e$ is invertible, to get $e^{-1}$. We get $e’$ from $u^{-1}$ or $f^{-1}$ in a similar manner. Since $e’$ will turn out to already be in the right direction, we will not require it to be invertible. Finally, given any 4 pairs of adjoints that look like the above, along with natural transformations $u,f,e,e’$ satisfying the above properties, we will get a distributive law!

What next?

Beck ends his paper with some examples, two of which I’ve already mentioned at the start of this post. During our discussion, there were some remarks on these and other examples, which I hope will be posted in the comments below. Instead of repeating those examples, I’d like to end by pointing to some related works:

-

Since we’ve been talking about Lawvere theories, we can ask what distributive laws look like for Lawvere theories. Cheng’s Distributive laws for Lawvere theories, which I’ve already referred to a few times, does exactly that. But first, she comes up with 4 settings in which to define Lawvere theories! She also has a very readable introduction to the correspondence between Lawvere theories and finitary monads.

-

As Beck mentions in his paper, we can similarly define distributive laws between comonads, as well as mixed distributive laws between a monad and a comonad. Just as we can define bimonoids/bialgebras, and thus Hopf monoids/algebras, in a braided monoidal category, such distributive laws allow us to define bimonads and Hopf monads. There are in fact two distinct notions of Hopf monads: the first is described in this paper by Alain Bruguières and Alexis Virelizier (with a follow-up paper coauthored with Steve Lack, and a diagrammatic approach with amazing surface diagrams by Simon Willerton); the second is this paper by Bachuki Mesablishvili and Robert Wisbauer. The difference between these two approaches is described in the Mesablishvili-Wisbauer paper, but both involve mixed distributive laws. Gabriella Böhm also recently gave a talk entitled The Unifying Notion of Hopf Monad, in which she shows how the many generalizations of Hopf algebras are just instances of Hopf monads (in the first sense) in an appropriate monoidal bicategory!

-

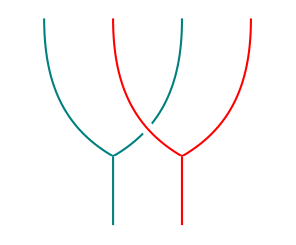

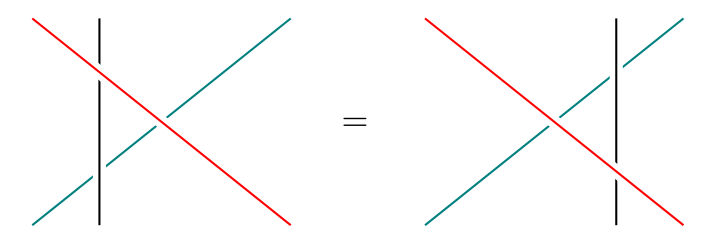

We also saw that distributive laws are monads in a category of monads. Instead of thinking of distributive laws as merely a means of composing monads, we can study distributive laws as objects in their own right, just as monoids in a category of monoids (a.k.a. abelian monoids) are studied in their own right! The story for monoids terminates at this step: monoids in abelian monoids are just abelian monoids. But for distributive laws, we can keep going! See Cheng’s paper on Iterated Distributive Laws, where she shows the connection between iterated distributive laws and $n$-categories. In addition to requiring distributive laws between each pair of monads involved, it is also necessary to have a Yang-Baxter equation between every three monads:

- Finally, there seems to be a strange connection between distributive laws and factorization systems (e.g. here, here and even in “Distributive Laws for Lawvere theories” mentioned above). I can’t say more because I don’t know much about factorization systems, but hopefully someone else can say something illuminating about this!