Tensor associated to a database

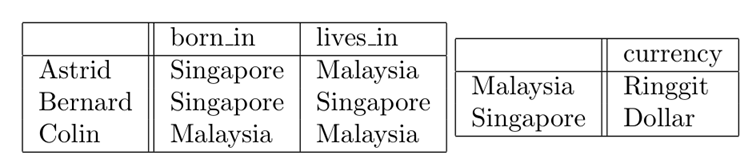

In this post (the 2nd in this series on Tensors and Language Models), we will be interested in collections of tables or dataframes that look something like:

We will call these databases. This example database comes from the paper on quantifying the knowledge capacity of attention layers.

By the end of this post, we will see how to define a tensor associated to a database. But first, we will begin by defining a matrix associated to a function $f: X \to Y$.

Matrix representation of a function

Suppose we have a set $X = {a,b,c}$, another set $Y = {m,s}$ and a function $f \colon X \to Y$ given by

\[\begin{align} f \colon X &\to Y \\ a &\mapsto s \\ b &\mapsto s \\ c & \mapsto m \end{align}\]Functions are columns in databases. For example, $f$ above is the column born_in if we replace $a$ with Astrid, $b$ with Bernard, and so on. For such a function, we may define an $|X| \times |Y|$ matrix, $M_f$, with entries given by:

For the function $f$ above, we would have

\[M_f = \begin{array}{c@{}c} & \begin{array}{cc} m & s \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) \end{array}\]The matrix $M_f$ represents the function $f$ in the following sense: let elements of $X$ be represented as vectors $e_a = (1,0,0),\, e_b = (0,1,0),\, e_c=(0,0,1)$ in $\mathbb{R}^{|X|}$, and elements of $Y$ as vectors $e_m = (1,0),\, e_s = (0,1)$ in $\mathbb{R}^{|Y|}$ (i.e. one-hot encoding), then we have

\[e_x \, M_f = e_{f(x)}.\]For example, one can verify that $e_a\, M_f = e_s = e_{f(a)}$. Thus $M_f$ stores the values of $f$, and can be used to compute $f$.

The rank of $M_f$

Since $M_f$ is a matrix, we can compute its rank. There are a few equivalent definitions for the rank of a matrix, but we will use the one that generalizes most easily to tensors, since tensors are where we’re headed next.

In order to state this definition, we first define a rank-1 matrix to be a non-zero matrix that can be expressed as a matrix product $c \cdot r$ of a column vector $c$ and a row vector $r$. The following example shows a rank-1 matrix and its decomposition into $c$ and $r$:

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \end{array} \right)\]The rank of a matrix $M$ is then the smallest $k$ such that $M$ can be expressed as a sum of $k$ rank-1 matrices.

From this, we can see that an upper bound for the rank of $M$ is simply the number of non-zero entries it has, since $M$ can be expressed as a sum of matrices that contain only 1 non-zero entry. For example, the matrix $M_f$ above can be written as the sum:

\[M_f = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right)\]and thus $\mathrm{rank}(M_f) \leq 3$.

But in fact, the rank of $M_f$ is 2, because this is also a rank 1 matrix:

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \end{array} \right)\]and we can decompose $M_f$ as

\[M_f = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) + \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right).\]In fact, for any function $f : X \to Y$ between finite sets, we can always decompose $M_f$ into a sum of $k$ rank-1 matrices, one for each element in the range of $f$, so that we have:

\[\mathrm{rank}(M_f) = |\mathrm{range}(f)|.\]We thus see that the rank of $M_f$ gives us some notion of the size of $f$.

Why matrices? Why rank?

But why go through all that trouble? Why not just represent $f$ as a dictionary or hashmap, such as f = {'a': 's', 'b':'s', 'c':'m'}?

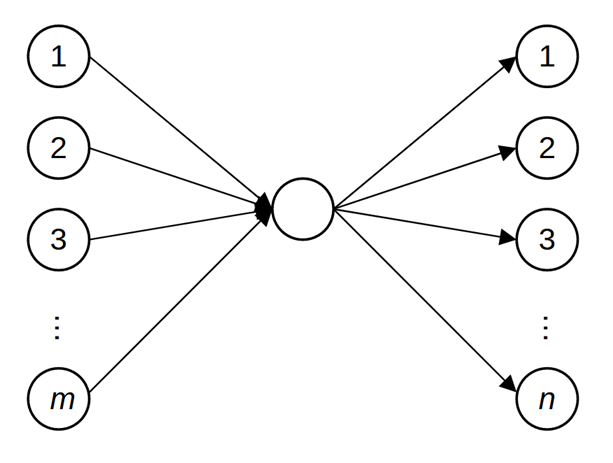

The reason is that linear algebra is the language of neural networks and multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs). Indeed, a rank-1 matrix $M$ can be represented as an MLP with 1 hidden neuron, where the activation functions are all just the identity function:

If $c \cdot r$ is the decomposition of $M$, the weights on the left are the entries of $c$, while the weights on the right are the entries of $r$.

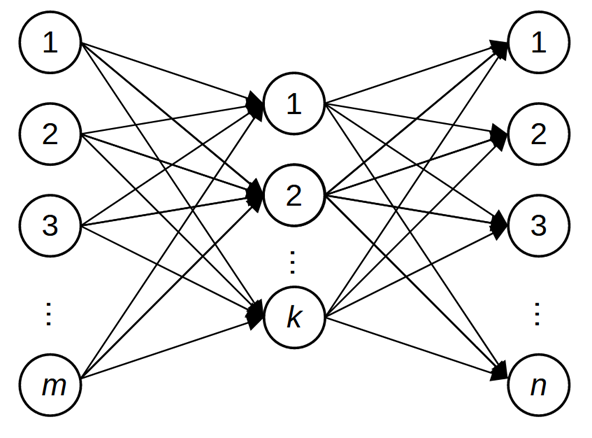

A rank-$k$ matrix is then an MLP with $k$ hidden neurons:

So the rank of $M_f$ tells us how many hidden neurons are needed to represent the function $f$ when using a linear network (i.e. a network with identity activation functions).

Of course, “real” MLPs usually have non-linear activation functions (such as ReLu or various sigmoids). As this paper shows, such networks also store functions (or “key-value memories”). If we record which outputs we get when we pass inputs of $f$ into the network, we should expect to get a matrix that is similar to $M_f$. In this setting, the number of hidden neurons continues to be a useful measure of the size or capacity of a network, even though it may no longer be the same as the rank of $M_f$ due to non-linearity.

From functions to databases

So far, we have seen that functions (or key-value pairs, associative memories, dictionaries, hashmaps etc.) can be stored in matrices/MLPs. But functions or key-value pairs are not yet facts. Here’s what I mean: consider the key-value pair (Michael Jordan, Basketball), which is sometimes given as an example of a “fact”. Indeed, Michael Jordan is most strongly associated to basketball, and if you asked someone to imagine “Michael Jordan”, chances are they would imagine him playing basketball or in a basketball jersey.

But what is happening here is that we are implicitly filling in a relation between Michael Jordan and basketball, such as played (for most of his career), or is most often associated with. And the facticity of the pair depends on this relation. If we change the relation to something like played in 1994, then the correct fact should mention baseball instead of basketball.

To put it another way, a function or a set of key-value pairs is only one column in a database, and a fact consists not only of a key-value pair, but also the name of the column, which indicates the relationship between the key and the value. Going back to the example database at the top of this post, the pair (Astrid, Singapore) is an incomplete fact. The full fact is (Astrid, born_in, Singapore).

Since a database is a collection of functions (one for each column in the database), and each function can be represented as a matrix, it stands to reason that a database can be represented as a collection of matrices, or a tensor.

Tensor representation of a database

A tensor is a higher dimensional analogue of a matrix. Just as a matrix (or 2-tensor) can be thought of as a collection of vectors (or 1-tensors), a 3-tensor is a collection of matrices.

We’ve already seen what the matrix for the born_in column looks like. Here’s the matrix for the lives_in column:

We get a 3-tensor by stacking these two matrices (think of them as lying on different pages of a 2-page book).

Meanwhile, the matrix representation of the currency column looks like this:

To stack this with the other two matrices, we need to pad them with zeros so that their shapes agree:

\[M_\beta = \begin{array}{cc} & \begin{array}{cccc} m & s & r & d \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \\ m \\ s \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) \end{array}\] \[M_\lambda = \begin{array}{cc} & \begin{array}{cccc} m & s & r & d \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \\ m \\ s \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right) \end{array}\] \[M_\chi = \begin{array}{cc} & \begin{array}{cccc} m & s & r & d \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \\ m \\ s \end{array} & \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right) \end{array}\]Here $\beta$ is the column born_in, $\lambda$ is the column lives_in and $\chi$ is the column currency.

Stacking these 3 matrices together gives us the $3 \times 5 \times 4$ tensor associated to this database.

For the general definition, it helps to think of a database as a collection of RDF triples. Although RDF triples are usually in (subject, predicate, object) or (key, query, value) format, for the purpose of this post, it will help to think of them in (predicate, subject, object) or (query, key, value) format instead. For example, our database above could be represented as the following set of triples:

\[\begin{array}{ccc} born\_in & Astrid & Singapore \\ born\_in & Bernard & Singapore \\ born\_in & Colin & Malaysia \\ lives\_in & Astrid & Malaysia \\ lives\_in & Bernard & Singapore \\ lives\_in & Colin & Malaysia \\ currency & Malaysia & Ringgit \\ currency & Singapore & Dollar \end{array}\]If we let $\mathcal{D}$ be this list of triples, we may define a 3-tensor $D$ of the appropriate size whose entries are:

\[D_{qkv} = \begin{cases} 1 \mbox{ if } (q,k,v) \in \mathcal{D}, \mbox{ and}\\ 0 \mbox{ otherwise.} \end{cases}\]Just as the matrix $M_f$ contains all the information of the function $f$, the tensor $D$ contains all the information of the database $\mathcal{D}$.

Technical note: In the paper ‘Paying attention to facts’, the triples are in (key,query,value) format and the entries of $D$ are indexed by $k,q,v$ instead of $q,k,v$.

Summary and what’s next

In this post, we have seen how to represent a function as a matrix, and a database as a 3-tensor. We have also touched upon the relationship between functions and MLPs. Note that a database cannot be represented as a single MLP, because MLPs only store key-value pairs! But as we will eventually see, we can encode databases in the attention heads of transformers. (see the ‘Paying attention to facts’ paper to skip ahead)

While we have defined and computed the rank of $M_f$, we haven’t talked about the rank of tensors. That will be the subject of the next post. We will also see that tensor rank has some unintuitive properties (at least for those who are more familiar with matrix rank).

Getting involved

If this line of work interests you, please reach out in the comments below, or email me at liangze.wong@gmail.com. I would be happy to collaborate on topics related to interpretability and theory of language models, even if it does not involve tensors or factual recall.

If you are hiring (or know of anyone who might be interested in hiring) research scientists with my background, I am currently open to work, and am open to re-location!